For millennia, these forests have rarely been left undisturbed. This is the heartland of the Western Abenaki people, who have lived here for more than 12,000 years. Hillside pockets were burned to make clearings for settlement, or to lure deer to new tree lines. By the time of European invasion, extensive networks of trails and trade routes had already been long established. Beginning in 1000 A.D., agriculture began to take root in the fertile valleys and in small clearings, with practices and ideas coming from other communities living further south. Seeds were gifted and traded between Indigenous nations and families, with a rich variety of crops—squash, sunflowers, corn, ground cherries—grown in fields by villages.

But it wasn’t until the mass migration of White settlers in the late 18th century that the forest was almost altogether excavated to form the sweeping vistas that we are more familiar with today. In the decade following Vermont’s admission to the Union in 1791, nearly 70,000 settlers flocked to the region and doubled the state’s population. Much of the land, granted to speculators in colonial agreements, was carved up into property lots. The soils here are rocky, if anything else, but the settlers had been sold an idea of agricultural paradise by the landowners, who were eager to seek return on these newly established parcels. Some settlers moved into clearings left by Western Abenaki families after European invasion displaced them to the North. Others set to clearing the forest for farmland.

Early on, the trees were girdled; a strip of bark would be hacked away from the base of each tree in a narrow ring. Over several years, the roots would wither, cut off from the sugars made in the leaves.

In later years, the trees would simply be felled and left to dry over the winter. The land cleared faster this way.

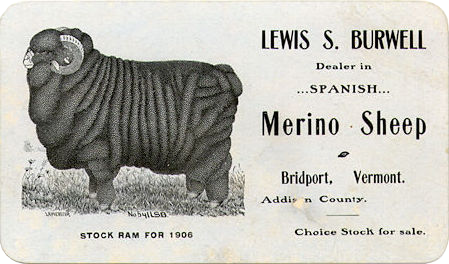

The logs would be sent down river to become lumber or burned to make potash. Even then, Vermont was overlain with pathways of global trade: the potash would be exported to England for use in its growing textile industry. For most settlers, the additional income went toward paying off the land.